I am an old man now with a sensibility that certainly frets about my grandchildren’s future but one that can still take delight in my own youth, even though, admittedly, I still cringe at the memory of a long list of painful missteps and awkward shenanigans. But through both the good and the bad my childhood was full and rich, no question about that, and the more I think on it, the more I realize how unusual it was. But the rural Texas that shaped my upbringing has now faded irretrievably into the rearview mirror, although this fact did not really sink in until many years later. A wave of nostalgia, yes, but I do wish to pass on to my children and grandchildren some sense of what is was like back then. I realize fully that this is a common impulse of older people everywhere and at all times who look around and say to themselves, “I don’t understand the world anymore,” but that realization takes nothing away from my desire to set something down on paper for the record.

At the time I thought it was normal to grow up semi-wild, like a Comanche Indian, to have my own pony with thousands of acres to roam on at will; to spend most of my youth in the river bottoms and post-oak savannah of south-central Texas, to develop an easy familiarity with the critters and varmints, the horses and cattle, and to come to adulthood in a rich and varied human-scape just as fascinating as the critter-scape. It was all captivating, but the human-scape was perhaps the most intriguing of all for me. It included a fascinating array of characters of all classes and colors; men who fit no mold and were often wonderfully eccentric and sometimes impishly irreverent. Citizens of German, Czech, and Anglo descent filled out the white population in roughly equal numbers, which created a unique dynamic within itself, but added to this was a substantial black population, which provided the most complex interaction.

Our little rural community of Smith Point replicated on a small scale the aforementioned demographic make-up of the county and this part of the state: Anglo, German, Czech and African American. At the time, it should be noted, there were very few Hispanic families in the county. Our own family counted as the Anglo component mainly because our immigrant antecedents were much older than the other groups and, in fact, were pre-Revolutionary War on both sides.

Our closest neighbors, the Richters, were of German ancestry. The grandparents, the grown son and wife, and their two sons shared the modest but neat farmstead across a country gravel road from our house. The family was almost completely self-sufficient with a large garden, hog pens, and a milking shed for the milk cows they kept. Emil, the old patriarch, still preferred German to English. His son Gordon and his wife Hildegard had two sons and the oldest of them, whom we called G-Boy, was my age, a constant playmate, and almost like a brother. This relationship was strengthened by the fact that we shared cousins, since my uncle had married into the family, and his children were first cousins to us both.

Further down the gravel road that ran between us, was a Bohemian family by the name of Kneblik, a wife and husband, who were childless, and who had set up a small farm, although both worked day jobs in the nearby town of Columbus. Although both native born, they preferred to speak Czech at home and the husband Nick only spoke broken English with a heavy Czech accent. Margie liked to bake Kolaches on the weekend. My brother and I and G-boy often ran down the road to sample these wonderful Czech pastries. We had to tell her, “Děkuji!” which means “thank you” in Czech. We also learned many German phrases since so many people knew the language and regularly sprinkled their conversations with words and phrases.

Even further down the gravel road was a freedmen’s colony, and the black people who lived there still spoke with a heavy accent called Gullah, which was hard for many white people to understand who had not grown up with it. There were several of these colonies sprinkled about in the county and usually not far from the Colorado River bottom where their slave ancestors had toiled on the large cotton plantations that spread up and down the river in the antebellum period. They had withdrawn to these enclaves after emancipation. This particular “colony,” which we called Frogtown, was dominated by the Scott and Field families and included five or six shotgun shanties clustered on a ten or fifteen acre tract. The families had a somewhat communal organization. I can remember a large cast iron pot in the center where the families would do their Saturday washing or render hogs for soap. The slave plantations, which had spread up and down the river in the antebellum period, accounted for the substantial black component, which had reached a high point of 45 % of the total population by the 1860 census. By the mid twentieth century this percentage had shrunk considerably as many blacks chose to “get out of Dodge,” so to speak, and seek better opportunities in the big cities or in the US military. Those who remained eked out an existence for the most part as domestics (women) or as farm and ranch laborers (me

Ironically, this led to a surprising degree of interaction on a daily basis between the races despite the rigid system of segregation that prevailed and that was designed to separate the races. It was still very much the Old South in rural Texas when I was coming up. Jim Crow reigned, and the old plantation mentality still prevailed among the white populations, but within this context meaningful and enduring relationships often developed that in some cases went back generations.

And so it was with us. We had a relationship with the freedmen’s colony down the road from our home. Claude Fields lived there and worked for my father several years before I was born. Later Lizzie Scott, the matriarch of the clan, and subsequently her daughters and granddaughters worked for my mother as domestic help. It went beyond that. My mother was the principal at the nearby Glidden rural school so when my brother and I were yet babies, Lizzie was our wet nurse and baby sitter while mother was at work, a kind of second mother. There were also many Blacjk cowboys back then, as good as they come, who often worked as day hire during the round-ups or on special occasions. It was a patron system. Black people had no chance for equal justice back then, so black families developed strong relations with important white families as a means of shielding themselves. “You mess with me and you be messing with Mistah Kearney,” that sort of thing.

The black component added another dimension and through the rich interplay of all these groups and characters who inhabited my youth, I developed an unusual facility, namely the habit of seeing and understanding the world through completely different eyes at the same time, and to accept the varied views as equally valid though they often seemed incompatible on the surface. This habit of mind reinforced my skeptical nature and has since crystallized into a philosophy for understanding the world and interpreting history. I call it the complementary view of life. I think it is a worthwhile habit of mind to cultivate because even as it broadens one’s own perspective, it encourages tolerance and discourages the narrow tribalism that is a source of so much evil in the world. In my own case it helped me in time to shed the ethnic and religious prejudices that surrounded me from an early age. The ‘complementary view of life’ is the common denominator to all the stories included below.

Jacob the Crow’s ungraciousness comes to the Rescue

Despite my semi-wild upbringing, I do believe I counted as a fairly dutiful child, and my good parents, especially my mother, did attempt to teach us proper manners and respectful deference to our elders, in other words, to outfit us with basic toolkits for civilized behavior. You see, good little boys do what they are told and believe what their elders tell them. I generally did what I was told as a kid, but from an early age I veered toward the skeptical side of life, Too many stories. Take religion. Our family was not a particularly religious, so it’s not like my budding incredulity was a form of rebellion against an overly spiritual upbringing. We did attempt to go to church occasionally, but this was more to keep up appearances than to satisfy deep-seated religious needs. Church was always a big production. Like most country boys, my brother and I felt awkward and self-conscious when dressed up, so it was always a struggle to get us properly washed and attired. My father, on the other hand, seemed to relish exchanging his working duds for a starched shirt and a pressed suit from time to time and it gave him an opportunity to hobnob. For mother, however, church was a serious undertaking but not for otherworldly reasons. Church was first and foremost a social event. Her ingrained sense of propriety demanded that she be properly clothed, bejeweled, and groomed for the coming public exposure; above all, a stylish hair-do was called for, requiring elaborate preparation, which, if in anyway interrupted, would upset our already strained timetable.

And so it was one particular Sunday. My brother and I had begrudgingly taken our places in the back seat of our ’54 Chevy Impala while Papa sat impatiently at the steering wheel waiting for Mama to put the final touches on her bouffant. We were running late, as usual. Finally, the back door opened, and out she came, obviously in a tizzy. Then as now, an ancient, patriarchal live oak tree overarched our whole back yard and one of its many spreading limbs dipped down to parallel the ground at a respectable height before turning up and issuing into a mass of leaves and branches over the back porch. This was the favorite perch of Jacob, our pet crow. Just as mother passed under him, with precise timing, Jacob released a slimy bomb that plopped with uncanny precision in the center of mother’s exquisite creation, which had culminated, fashionably, in an enormous bun on the very top of her head.

Mother reacted with horror and indignation, letting out a stream of very un-Sunday-like expletives directed at Jacob, who commenced to fly around the house squawking “bwekfas, bwekfas,” the only sounds he knew that any way resembled a recognizable human word. My father could only hold his sides in laughter, which made my mother even madder, but my brother and I were overjoyed, for we instantly realized that Jacob’s ungraciousness had spared us the torture of sitting through another interminably long and boring church service.

Jacob’s one word vocabulary had come about like this. My brother collected bird nests avidly and had assembled quite an impressive display in our train house (later) of which he was very proud. But his collection lacked a crow’s nest. One day he spotted one in a low post oak tree and shimmed straightaway up the tree to appropriate the missing prize. The parent crows were out foraging somewhere, which made the task easier, for they would have defended the nest vigorously. The nest had one baby crow in it. You can guess the rest. He brought the nest home along with the baby crow. We fed him successfully first with a milk dropper and then with bred crumbs until he got old enough to fly at which point he was banned from indoors.

Now the morning routine at our house called for papa to get up very early, around five o’clock, and fix breakfast, which was usually no more than buttered toast and occasionally scrambled eggs that were eaten on the toast. Once properly browned, he would yell at the top of his voice, “breakfast,” at which time everyone arose to greet the day. At one point Papa had split Jacob’s tongue because, so he maintained, that would make him better able to talk. Be that as it may, Jacob, upon hearing Papa yell, or any other excitement for that matter, would commence circling the house squawking, “bwekfas, bwekfas,” which constituted his one word vocabulary.

Jacob, unfortunately, only came to our rescue on this one occasion. Our preacher at the time was tall and gaunt with sharp, bird-like features: to youthful eyes almost demonic in appearance. His head was very bald and glistened in the light of overhead chandeliers. His most noticeable feature was a big bump, almost like a tit, smack dab on top of his shining pate. He was a true old-time ‘fire and brimstone’ type. Upon reaching the crescendo of his sermon, when he assured the assembled that they would all most assuredly roast in hell for eternity if they didn’t repent and change their wicked ways, he would lean out over the pulpit and gesture frantically with his long, bony fingers. His face would turn a ghastly red, beads of sweat would gather on his forehead, while the changed angle of presentation would create the impression that the bump on his head had undergone an erection. As he ranted and gesticulated, the ladies of the church would fan ever more furiously, as if to keep pace with the rising drama of the spectacle.

My parents didn’t seem particularly moved by the preacher’s theatrics and the reader can understand that this whole exhibition did little to further a proper appreciation for religion on my young and impressionable mind. Once the service was over, life quickly returned to familiar paths. Papa continued to swear like a sailor and mama reflected on how to readjust her wardrobe (and hair-do) for the next social outing. For my part, I didn’t spend a lot of time worrying about hell and redemption. Once out the door, I took a breath of fresh air to get the smell of sweaty humans out of my nostrils (pre-air-conditioning) and looked forward to shedding the unwanted duds and feasting on the promised post-church meal of fried chicken and dumplings with homemade biscuits, which was tradition in the family and the one real compensation for all this falderal.

I couldn’t understand why we didn’t just skip the church part and go straight to the chicken. But I guess I took more from this whole affair than I realized. Did you ever notice how closely a baby calf watches her mama? When a cow jerks her head up high, she is signaling the possibility of danger. Her calf will notice this instinctually and forever be wary of whatever the mama was looking at. But the reverse is also true: if the mama cow continues to graze indifferently while (say) a human walks by, the calf will assume from that point on that humans are tolerable. Human calves are no different: if my parents weren’t concerned with hell and redemption, why should I bother? They hadn’t jerked their heads up at the good preacher’s words or otherwise indicated through their deportment that they took his antics and words too very seriously, so I learned to take this sort of thing with a grain of salt.”

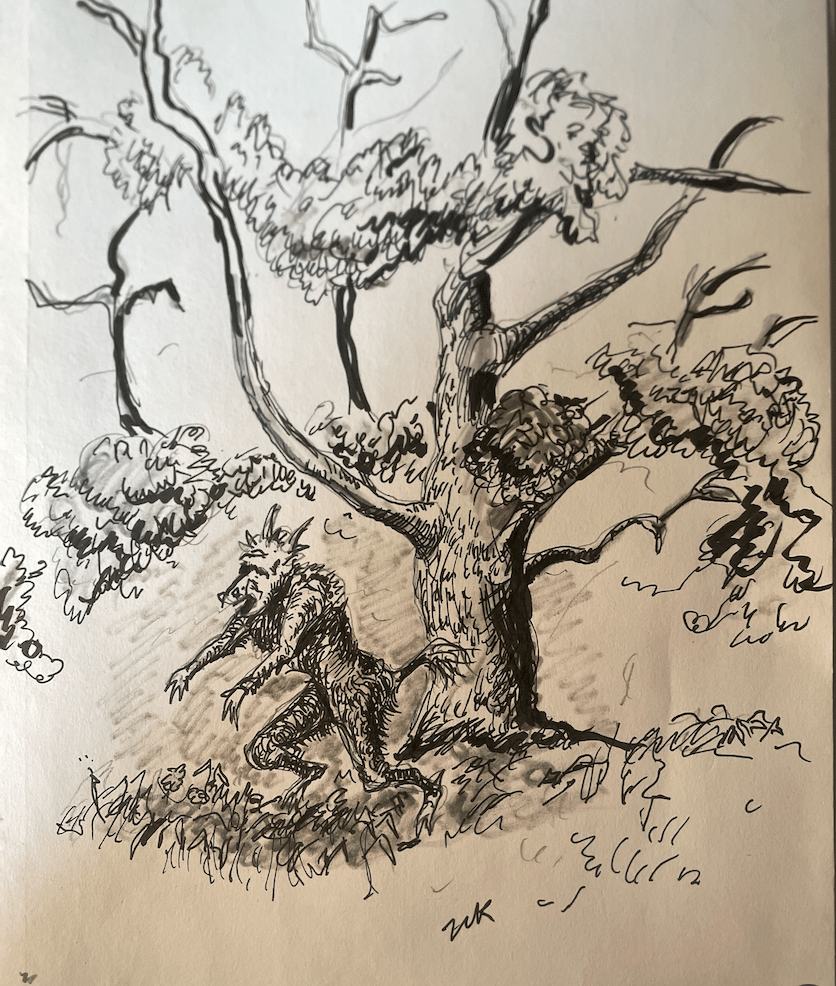

We did fear the unknown and the mysterious, however, and the thing we feared more than the preacher’s devil was the “Yelpin’ Stretcher.” Invariably, as we would bump along in Papa’s green ‘49 Chevy truck down the sandy country lane that separated the Home Place ranch, where we lived, from the larger ranch, which we called the 88, Papa would remark, “Look there he goes; it’s the Yelpin’ Stretcher!” He usually did this along that stretch of the road that passed through the Skull Creek bottom where numerous giant ash, pecan, and live oak trees overarched a swampy understory dotted with palmettos, which we called Spanish Dagger; a stretch of road that always evoked a mysterious, almost foreboding feel, especially at dusk when the last fading rays of sunlight filtered through the forest canopy accenting the gnarled and grotesquely twisted shapes of the ancient tree limbs. Gullible and credulous, we would strain our eyes to see, but always in vain, whereupon we would demand a full description from papa as to exactly what he (it) looked like. He would hint at but never describe fully, giving free rein to our youthful imaginations to fill in the details, which soon conjured up a creature with horns and tail; amazingly similar, in fact, to medieval depictions of the devil.

I have since discovered that the “Yelpin Stretcher” or variations thereof exist in many cultures and traditions and often serve a similar purpose, namely to enlighten (or frighten) children into a proper respect for nature and our place in it. The Iroquois had “Little people” while the Algonquian had “Wendigo.” Apparently, our “Yelpin Stretcher” has its roots in Appalachia (Tennessee) where my father’s father grew up. But this much is certain, as kids, the Yelpin’ Stretcher was alive and real for my brother and me; much more frighteneing than the invisible devil that our good preacher kept alluding to.

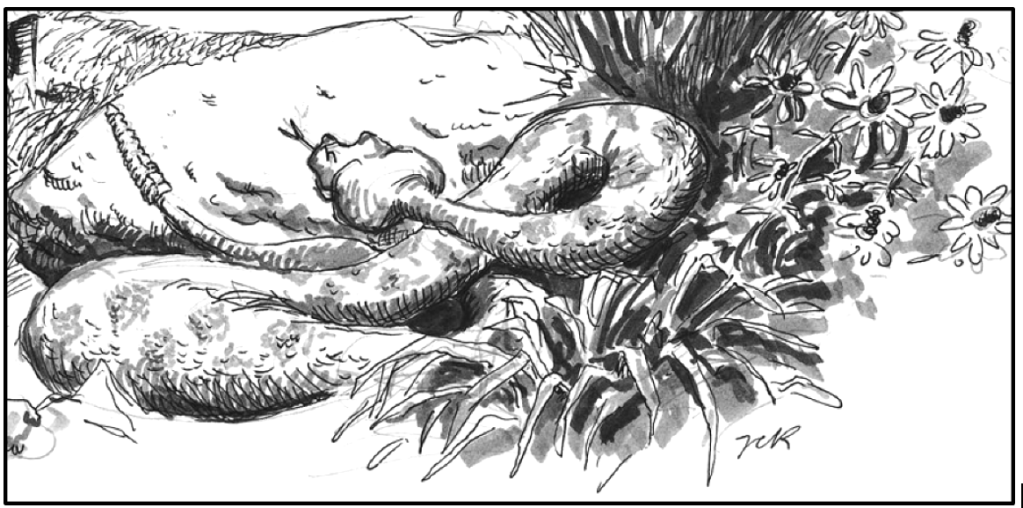

But some of our fears, unlike the Yelpin’ Stretcher, were grounded in hard reality, like rabies and snakes. Take Black Mike. Papa always kept a two or three snarly cow dogs, which were supposed to stay in a large dog yard that adjoined our back yard, but often had the freedom to roam about. We had a different relationship to dogs than most people do today. They were not cute, affectionate pets that we fawned over and to which we attributed human characteristics. They were working dogs, indispensable for gathering cattle out of the brush and keeping them together while we moved the uncooperative beasts on horseback toward the pens. And so it was with Black Mike, the meanest and snarliest of the pack, but he was a hellavu cow dog, a natural alpha. You see, all dogs are either headers or healers by nature, harking back to their pre-domesticated past as wolves when the pack would divide between those giving the chase and those waiting in ambush. Anyway, when we gathered cattle from the brush on horseback with the help of the dogs, bunched them, and drove them toward the pens, the herd would often balk at passing through the final gate into the trap that led to the pens. They sensed this was a place where bad things happened (from their point of view) and so they would often hesitate and refuse to pass through that last portal, and some of the more spirited ones would even try to make a break for freedom. This is where Mike would show his stuff. He would position himself in the gateway facing the cattle. Now even the tamest cattle, harking back to their pre-domesticated days, regard dogs as wolves and will instinctively bunch up for protection and turn to face their hereditary adversary, while the bolder ones, often feign short charges with head to the ground and tail in the air, and then retreat to the safety of the herd. These attacks are usually bluffs, but not always, because most of the cows were horned and if they happened to catch a dog on the tip it could mean instant disembowelment, which happened on occasion. But Black Mike was much too nimble, and always easily sidestepped or quickly retreated a step or two to parry the attack. This process, however, had the effect of moving the whole herd forward, one charge at a time, and eventually, with patience, would start the reluctant bunch moving in the right direction, and once a few individuals passed through the gate, the whole herd would then attempt to stampede through.

So, harking back to our Neolithic past, we kept dogs not to fawn over and serve as ersatz human companionship, but for their utility; and they, on the other side, accepted our overlordship only because we fed them and in the act of working cattle reproduced a scenario that evoked their natural instincts.

Rabies was a genuine concern for country people back then. Skunks were especially prone to the disease, and it seemed like not a summer passed that we did not have an incident with a ‘mad’ skunk wandering up to the house, showing no fear of humans and sometimes behaving unnaturally aggressive — a sure sign of the disease. But dogs were also prone to rabies since, given the opportunity, they will chase and kill small animals, like skunks, thereby contracting the infection. And you guessed it, Black Mike got rabies. He began lurking around the house and foaming at the mouth and acting very menacing. Noticing his odd behavior, papa realized right away what was up and told us all to get in the house and not come out. This was rather late in the day. Papa took down his trusty hunting rifle, a .270 bolt action he called his ‘slippin-slopper,’ and then, even as dusk settled over the scene, stepped outside to shoot Black Mike before he bit and infected either a person or another animal with the dreaded disease. In the meantime, Black Mike had left the yard and Papa had to go out and hunt for him in an adjoining pasture, which was brushy and wooded. Directly we heard a shot and in a little bit papa returned. We were of course eager to know the score, but papa said he was only able to get off a quick shot in the brushy twilight and had only wounded the dog, which had run off. Papa was confidant he would not survive the wound for very long, but the next day he could not find the dog and, in fact, we never found his body. You can imagine how this played out on our youthful imaginations. For years, I could not venture into that stretch of the woods after dark without senses sharpening, like a deer venturing to water and knowing his vulnerability. Black Mike was still out there somewhere waiting to get his revenge. And the sounds of summer in South Texas reinforced this fear. People forget how downright noisy the nights are in this part of the state. The crickets, the cicadas, the tree frogs, the screech and hoot owls, the occasional coyotes, the whippoorwills, you-name-it, all conspire to produce a cacophony of noise that is incessant, spooky, and unnerving, and that serves to stoke the imagination of a young boy in fear of rabid dogs and mysterious Yelpin’ Stretchers. Mother nature is wondrous but there are aspects of it that are out to get you and that was an important lesson for young kids who grew up close to her.

Gen Z and probably a couple of gens before them have lost meaningful connections with the food they put in their mouths and the plants and critters behind that food. That’s a big change from when I was coming up when people were closer to the land, many only a step removed from the farms and ranches they grew up on. Pante Re, things change, so it is not surprising how many today have not a clue when it comes to the cattle that supply so much of the food they consume whether in the form of meat, cheese, or milk and the clothes they wear in the form of leather. They generally regard cows as large, dumb beasts more akin to docile pets than wild animals.

Not always true. Take the storied longhorns of Texas. They escaped from the early Spanish colonists and conquistadores to thrive and propagate by the thousands on the open prairies even as they took on certain distinctive characteristics. Their unusually long horns made them stand out as a breed, but they also evolved to be ornery, rangy, and mean. Consequently, once cattle became valuable after the Civil War, Texas ranchers began looking to other breeds, especially the English breeds that are as a rule more beefy and less cantankerous, but it was soon discovered that the English breeds did not fare so well in the heat and humidity of South Texas., a climate radically different from the cool, moist British Isles that they had called home. On the other hand, Brahma cattle seemed to thrive in these conditions. This was because bos indicus evolved on the subcontinent under similar conditions to South Texas and so found themselves well adapted to their new home.

Around 1880, the storied Texas cattleman Shanghai Pierce of Wharton County, was the first to import Brahma cattle from India. Other ranchers took notice, and the breed spread rapidly. Brahma cattle are larger framed than the native longhorns, but not as beefy as their European counterparts. They also exhibit a personality that differs markedly from most European breeds. If undisturbed they can be very docile and approachable, but they can shed their tameness on a dime and assume a wild and even dangerous disposition when molested, especially when they feel their calves are threatened.

Texas ranchers soon discovered, however, that if they crossed bos taurus with bos indicus they got a superior animal that combined the beefiness of (say) a Hereford with the heat tolerance of a typical Brahma cow. Thus was born crossbred cattle, the preferred breed of South Texas, and the kind of cattle I grew up with. Many variations soon emerged, depending on what breed of European cattle a rancher chose to cross with bos indicus. These different combinations solidified over time into several established breeds common to Texas such as Santa Gertrudis, Brangus, and Braford, to name three of the more prominent. All these breeds, however, aimed at institutionalizing the remarkable hybrid vigor that comes with the initial cross, but, alas, in so doing ranchers ignored a basic genetic truth, namely that hybrid vigor only comes with the first cross; it cannot be made permanent by (say) breeding one F-1 product with another.

For my money, the preferred first cross, was (and still is) the much desired “Tigerstripes,” named for their distinctive tiger-like stripes. Tigerstripes result from breeding a Brahma bull with Hereford cows. The other way round produces something different. These cattle live longer, exhibit fewer genetic flaws such as blown udders, and tolerate the heat, humidity, and insects of South Texas almost as well as pure Brahmas. They can also be very temperamental, and they don’t like it when humans mess with their calves, which happened a lot because of the scourge of the screw worm fly. Cattlemen had to be constantly on the lookout for infestations especially in newborn calves. The mama cows saw our interventions as a threat and reacted accordingly. A few would simply go rogue after a while and decide that all humans were their enemies who needed to be avoided, if possible, and preemptively attacked, if cornered. They would not come to feed and we could only gather them with dogs and horses, which could be a hair-raising experience, and even then, they often got away.

A cow gone “framey

We had a word for this. We called it “going framey”. Framey Point was a hundred acre thicket, thick as hell, where a tick needed to low-crawl to get through in places. At one point a little herd of frameys had gathered there and managed to avoid any contact for several years. The herd included a bull so that they perpetuated themselves and were on track to revert to pure aurochs, the wild precursors of all European breeds, which survived on large aristocratic hunting estates in Lithuania until the 18th century.

These were the cattle I grew up with. Prized for all the traits outlined above, when it came to handling them, they were in a different league from the docile European breeds and required a whole new set of skills. When working them, the adrenalin often flowed for man and beast. We eventually cleaned up the framey bunch, but it involved roping one miscreant at a time (see picture) and field loading each beast into a cattle trailer. A feat that required good horses, working dogs, and skilled cowboys.

As mentioned, their temperamental nature was made worse by the scourge of screw worms, and here a word of explanation is in order since most people today have no idea what I am talking about. Screwworm infestation was a major threat to the Texas cattle industry when I was growing up. The screwworm fly (Cochliomyia hominivorax) is notorious for laying eggs in open wounds of living animals, where the larvae feed on living tissue, often leading to severe wounds, weight loss, and eventual death if left untreated. It was a scourge that led to the deaths of hundreds of thousands of animals every year. A single drop of blood left by a horsefly bite or a scratch from a thorn could lead to an infestation in cows, but young calves were especially vulnerable. This was because the young calves are born with blood on their navels which attracts the flies and leads to open putrefying wounds. A substantial percentage of newborn calves would become infected each spring in this manner. The mothers often could not care for their young and it required timely intervention on the part of ranchers to prevent death and economic loss. The economic and operational burden of the screw worm scourge on ranchers was immense. Treatment was labor-intensive and unpleasant, requiring constant inspection and application of foul-smelling insecticidal treatments to wounds. The most well-known formula was ‘Smear 62,’ a foul-smelling and noxious blend of pine tar and lanolin. It had a very distinctive odor that is seared into my memory. It was effective but the creosote in the blend burned terribly and caused young calves to bleat pitifully upon application further infuriating their mamas.

Screw worm infestations are a thing of the past (at least we hope so) and over the past fifty years or so the trials and tribulations associated with it have largely faded from memory. The turning point came in the 1960s with a USDA program that involved releasing massive numbers of sterilized male flies with airplanes to suppress the wild population. A facility was set up in South Texas to raise and sterilize the flies by irradiating them. This innovative approach led to a coordinated, decades-long eradication campaign across the southern U.S. and into Mexico. The facility, however, produced a horrendous stench and with US money was eventually relocated to Central America where it continues in production to this day.

Papa had two basic approaches for dealing with screw worms on the ranches he either owned, managed, or leased: he either doctored individual cases in the field or he would gather a herd (or bunch, as we termed it), pen them, and then use the tools of the corral such as squeeze chutes, snubbing poles, or crowding lanes to doctor the animals. The full-grown animals required this approach for obvious reasons. We often doctored calves individually in the pasture. This would require at least two riders: one to rope the calf and the other the keep the calf’s mama at bay.

Lascaux Cave in France with Neolithic depictions of aurochs

Black Mack was a large, crossbred bull that had an eerie resemblance to pictures of the last remaining Aurochs that survived on the large aristocratic estates in Poland and Lithuania well into the 17th century. He had a dark cast to his hide and very powerful, shiny black horns that were meant for business. Yep, you guessed it, Black Mack went framey. It began when he took a dislike to Cholly whose task it was to feed the cattle on the Home Place using an old Ford 8N tractor and a trailer stacked with small hay bales. Cholly would load the trailer full in the barn then drive out in the pasture, bust the bales open one at a time and spread the sections out so that all the cows got a chance at the hay. For some reason this simple activity began to irritate Black Mack, and he commenced to act more and more aggressive. He also took a particular dislike to the small 8N Ford tractor that Cholly used to feed the cows. It came to a head one day when Cholly towed a load of hay into the pasture to feed the cattle. Mack placed himself square in the center of the road in a threatening posture. Cholly yelled at him to get out of the way and when he refused to move, he yelled, “You get yo’ black ass otta da way or I’ll run you ober!” But Black Mack stood his ground with his head on the ground. When the tractor got to him, he jerked his powerful head and horns up and almost flipped the tractor over backwards. The tractor stalled and Cholly sought refuge on the hay trailer and stayed there until Black Mack had satisfied himself that he had vanquished the unwanted machine (and human) that had strayed into his domain. Cholly quickly restarted the tractor and made a beeline for the safety of the barn and runaround.

But my brother and I had a more personal encounter with Black Mack which led to his demise. We were playing in the runaround[1] one day, and the gate was open to the outside pasture. I wasn’t but two or three years old and my brother was eighteen months older. Black Mack wandered in the enclosure and when he spied us, he started toward us at a trot. Luckily our father was nearby and sprang into action. He quickly took first me and then my brother and flung us over the chain link fence to the safety of the house yard on the other side. He then turned around to face Black Mack who was almost upon him with head down and tail up in a full charge. Instinctively, he jerked the Stetson off his head and sailed it to the ground in front and to the side of the enraged beast. An old trick, known to all cowmen but it worked. Black Back went for the hat which gave Papa just enough time to put a big post oak tree between himself and the furious bull. Black Mack tried to get him, but Papa was too nimble and after a bit of fancy dancing around the tree, the bull gave up and retreated far enough for Papa to make his retreat to the safety of the yard. All’s well that ends well, but Black Mack had crossed the line. Papa went straight into the house, fetched his trusty ‘slip-n-slopper’ (270 rifle with a Mauser action and a set trigger) from the gun cabinet and dropped Black Mack dead with one well-placed shot. Papa cut his massive horns off and for years they hung in the saddle house. A few years back my daughter took them to a taxidermist and had them cleaned up and mounted on a board where they now grace the fireplace at her family’s house in San Antonio. Black Mack is long gone but not forgotten for the horn’s remind ne of a very close encounter that could have been deadly.

Ol’ Herb

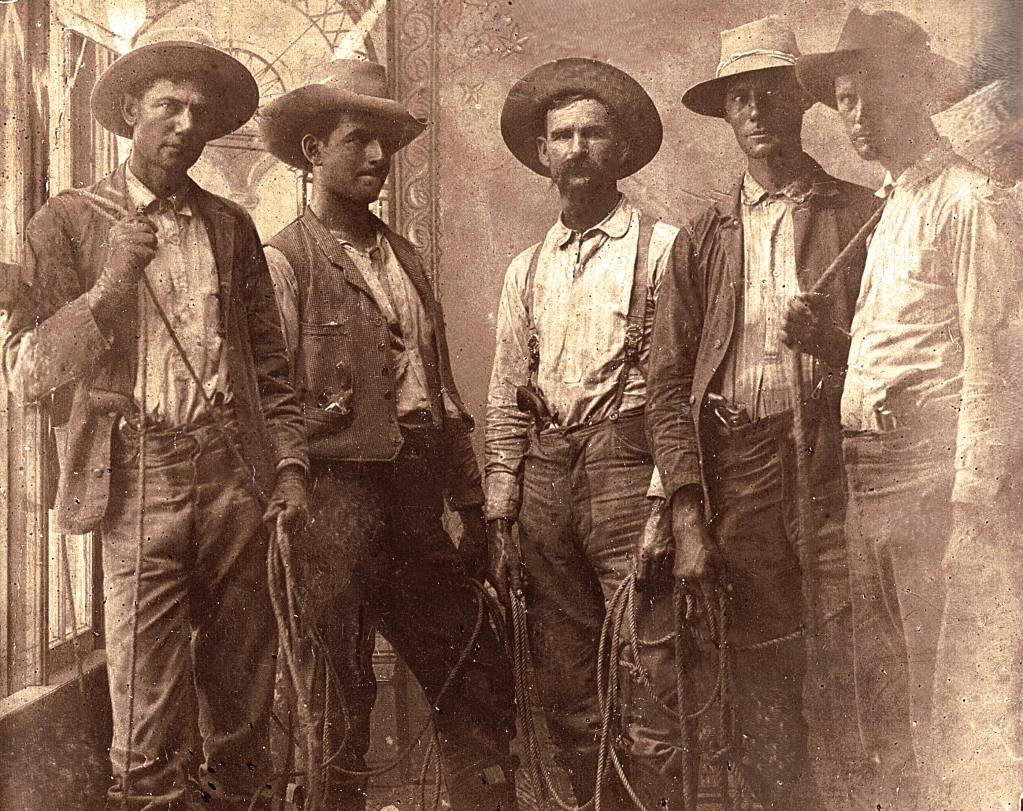

A lot of bull stories to tell. Some I experienced personally, and some have passed down through the family, like the story of Ol’ Herb and the rogue bulls. It was in the depths of the Great Depression and a man did what he could to earn a little hard cash. Papa’s neighbor, Mr. Auerbach, had two rogue bulls that he could not pen. He offered papa $10 a head to anyone who could pen them could pen them and haul them to market, good money for the times. Papa took the challenge and called on a black cowboy by the name of Ol’ Herb who helped him from time to time and though beyond his prime was still as good as they come. He was the one people called on for the really dicey jobs. They saddled up their horses and with a couple of good cow dogs, set out to pen the bulls. They found them in a stand of open post oaks. Spotting the riders and with the dogs on their tails, they broke and ran, each taking a different course, heading for thicker brush and safety. Papa yelled to Herb, “You take the brindle, and I’ll take the muley,” and each headed off at a full run with their ropes ready in hand. Herb was the first to catch his bull, making a good throw with the loop of the rope settling effortlessly around the neck of the fleeing beast. Herb hadn’t lost his touch. But just as he threw slack and the noose tightened, the bull darted around one side of a post oak tree and Herb and horse, ducking limbs, slid to the other side at a full run. The crashed together on the other side when the tree pulled slack on both, slamming the horse with rider and bull together in a horrible collision. The force of the blow brought both horse and bull to the ground in a tangled heap and launched Herb through the air a good twenty feet where he struck the ground with such force that he was knocked out cold and appeared to be dead. In the meantime, Papa had lost his bull in a thicket and returned to help Herb but found instead the bull and horse still entangled and Herb nowhere to be seen. Papa quickly cut the rope binding the two beasts together and called for Herb. He found him under a yaupon bush nearby and rushed to his side and tried to revive him. He finally came to his senses somewhat but without saying a word began bucking and pitching on all fours like a rodeo horse. Then he keeled over and died. A hard way to earn an extra dollar but an appropriate demise for a man who had spent his life on horseback dealing with outlaw cattle.

Clifford and the Stags

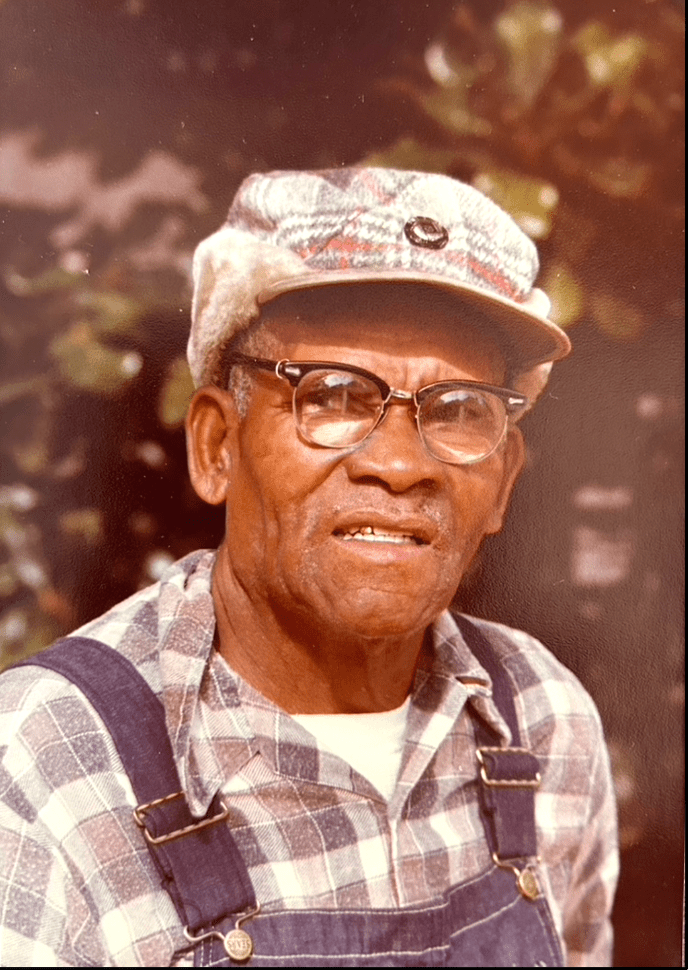

The Kearneys and the Wegenhofts go way back. Johnny Wegenhoft on the right in the picture was the grandfather of my neighbor Travis Wegenhoft who is now in his eighties. Our families have been neighbors for close to a hundred years now and both families have been in the cattle business for the whole time. Some of their stories have come down to us as well and here is one of them, but it was told to me by Clifford Austin, the black cowboy featured in the story. Although he was an old man by then, I used to hire him occasionally when I worked the cattle on a lease pasture near Altair where he stayed. He wasn’t really expected to do anything. I just liked having him around and listening to his stories of cowboying and cowmen. He was a voice from the past and I listened with relish to his many stories. He worked for the Wegenhoft brothers for many years. The story below is short but sums up the relationship of a working cowboy to his horse when dealing with wild cattle.

The Wegenhoft brothers had bought a full truckload of bulls at a discount, some old and useless, but most because unruly and even dangerous as crossbred bulls are wont to become at that stage of their lives when still serviceable as bulls but nearing the end of their usefulness. The idea was to stag them, turn them out in a river bottom pasture, put on a couple of hundred pounds of weight each and then sell them in six months or so for a quick turnaround. A good plan in principle, but in practice not so good. Stagged bulls are not the same as oxen. Oxen are castrated at an early age before the testosterone flows and so have no recollection of their manhood. They are usually docile and grow large and fat because no energy wasted fighting other males and chasing heifers. Stagged bulls, on the other hand, are what the old-timers called ‘proud cut.’ No longer able to reproduce, they still have strong stirrings of their manliness and often grow even more cantankerous and unruly out of frustration.

And as summer turned to fall, the day came to gather them from the pasture they had been turned into the previous spring and haul them to market for the anticipated profit. Three trucks with trailers lumbered into the pasture before the break of day with the morning dew still heavy on the grass and the six cowboys unloaded a pack of excited cow dogs and their already saddled horses. A heavy fog hung over the landscape and as the grey, dull sky began to show some signs of color. When the fog lifted from the river bottom, a frightening sight unfolded below. The stags had come up from the river bottom below to face their adversaries.

Clifford Austin was one of the cowboys whose job it was to pen this crowd of snorting, angry stags eager for a fight. Clifford had been a cowboy for hire all his life and despite the system of segregation he had grown up in, had earned a begrudging respect. Astride his horse, he was a full equal. This time, however, he rode a young mare which had not yet conceded fully that Clifford was her master. Seeing the stags that had come up to meet them and do battle, Clifford leaned over to his mare, and gently said, ‘Now Molly today you and me gotta be of the same mind or it gwina turn out bad for us both.”

Unc’s Blasphemy

Most of the characters that populated my youth were rooted to the land in one way or another. Many were, wonderfully irreverent, which reinforced my doubting nature. Take for instance “Unc,” as we all called him. Unc and my father ran cattle together on one of the many pastures that papa either owned, leased, or managed; it was all the same to us at the time. Unc resembled Santa Claus. He had a ruddy complexion and keen blue eyes. He was also a bit portly and always wore suspenders to keep his baggy khaki pants up. He also stuttered. When a heat shower would come up in the summer and the lightning would start popping, he would invariably look up to the sky and, with a twinkle in his eye, say: “Rrroll them bbbarrels, you ssson-of-a-bbbitch!” Joel, his side-kick hired hand, a black man who always wore sunglasses to hide an ugly scar to his right eye, would invariably counter, “Now Mistah Warner, that be blasfommy; lightnin’ sho’ nuff gonna strike you dead one of these days,” at which point he would remove himself a respectful distance just in case his prediction came to pass. Joel, subsequent to a miraculous recovery from a love gone wrong self-induced injury, had gotten religion and hence his concern. His prediction of divine retribution in the form of a lightning strike, however, never materialized, but the interaction with blasphemous ‘Unc’ was constant and didn’t go unnoticed. For his part, Unc lived to a respectable old age and dropped dead one day from a heart attack without to my knowledge ever having set foot in a church during his adult years. He passed from this earthly existence with no fear whatsoever about roasting in hell for eternity. The outdoors was his church and the natural rhythms of life his only guide and comfort. You pick up on that as a kid.

My brother and I had a second father, a black man by the name of ‘Cholly.’ Cholly was to my father as Joel was to Unc: on the surface a hired hand but more a life-long companion and sidekick. He was constant presence during my whole childhood. Cholly lived and embodied an utterly different sensibility about people and life, which, on the one hand, came out of his own eccentricities, to be sure, but, on the other hand, represented a reflex to his situation as a Black man in the still very much segregated South. I only came to appreciate this latter point much later.

The whole world, including religion, passed through his eyes and filtered through his consciousness to come out in a unique blend, like a magic sausage concocted of common ingredients but blended in a wholly new way by a marvelous, mysterious sausage grinder.

Except for a noticeable deformity, Cholly could have passed for a tight end in the NFL. He was tall, long-limbed, and powerfully built. He had the largest hands, I believe, I have ever seen on a human being. Unfortunately, he had been born with a club foot, which gave him a noticeable limp and precluded any kind of organized sport activity. Still, he was incredibly strong and well-coordinated. We were building a set of cow pens once and each board required five nails where it attached to a post. Cholly would always start all five nails first and then rapidly hammer them, using two hammers, one in each hand, striking each in rotational sequence with nary a miss. This was very impressive to me as a boy and a feat I certainly could never duplicate and never saw anyone else duplicate for that matter. He had also developed an extraordinary adroitness with a hammer as weapon. Papa set him to work a good part of every summer riding an open tractor shredding weeds. He often pulled up to the house after a day’s effort with a couple of jack rabbits swinging from the side of the machine which he had dispatched by throwing a hammer that he kept strategically located on the floor board. His aim was unerring. He would take the rabbits home for the evening meal.

Papa and Cholly had a classic love-hate relationship. Cholly had absolutely no understanding or patience for things mechanical, like tractors, and his missteps in this regard were legendary. I remember once he put cold water in the radiator of an over-heated tractor—something even I knew not to do—and cracked the block. Papa cussed and stormed and berated Cholly to no end, which he patiently endured, but there was never any question of serious repercussions, like firing. This was understood. Cholly had ingrained himself into our existence and his transgressions were always pardoned with time.

He was always around, often just to accompany Papa in his pickup as he made the rounds to the numerous cow pastures and hayfields that he oversaw. His role was simply to be a companion and open and shut the numerous gates and wire gaps in the various pastures. Papa and Cholly were exactly the same age and they both had handicaps, my father having lost the use of his right hand in an electrical accident many years before.

Cholly and the Bellboys

Many stories connected with Cholly have passed down in the family. One never failed to entertain and that often made the rounds during hunting season was about Cholly and the electrified “bellboys.” It concerned an ill-considered trip deep into the Skull Creek bottom in the search of a missing bull before the poorly drained bottomlands had adequately dried from the spring rains. As Papa and Cholly drove ever deeper into the creek bottom, winding their way through the ancient overarching live oaks and ash trees laden with Spanish moss, Cholly grew more anxious and implored Papa to turn around. “What we gonna do if we get stuck and it turn dark?” he said, “and the bell boys be out?” ‘Bell boys’ was his term for the timber rattlers who were common in the bottom, and often grew to enormous dimensions, some over seven feet in length. But Papa was determined to find the bull and didn’t take heed of his concern. Sure enough, they had not gone very far when the truck became hopelessly mired between two enormous ash trees in a particularly treacherous mud hole in a sharp turn in the rutted path we called a road. It was late in the day and they were miles from a public road. With the little bit of daylight left they attempted to jack the truck up and place sticks in the ruts under the wheels, but to no avail. As the moonless darkness descended over them, intensified by the overarching canopy of enormous hardwood trees, which formed an effective shield to the firmament above, Cholly announced, “I ain’t gonna walk outta here, bell boys ‘ll get me.” Papa replied, “Suit yourself, but I am leaving, “ and with that he lit out at a fast walk. He hadn’t gone four steps when Cholly fell in behind him, step for step, “I ain’t stayin’ here by myself; the haints [spooks] be out!” The two stumbled along like this for miles, it seemed, trying to retrace in the dark the muddy path they had driven over in the truck. But it did not take them long to get lost and disoriented in the pitch-black night. They strained to pick up the sounds of the trains at the switchyard in Glidden four miles to the north. The whistling and clanking of the steam engine and cars would carry effortlessly for miles through the night air, giving a sure bearing when the North Star remained hidden. And sure enough, though hopelessly lost, they picked up the sound of the trains and struck a beeline toward them in the expectation that they would have to eventually encounter the public road that would lead them to a farmhouse and a phone where they could call for help. In this hope they crossed a fence and stayed out into a field that appeared to be largely free of underbrush and trees, which lifted their spirits since it hastened their progress. Suddenly something struck my father at the knees, who was still in the lead. He felt a sharp sting, followed by another and another. He fell to the ground flailing with his hands and arms at the unknown attacker, crying out in surprised horror at the unknown assailant(s). At this, Cholly turned tail and lit off at an angle as fast as his clubfoot would allow to escape the mysterious fiend, but to no avail. He too felt the fiery sting hit both his legs beneath the knee at the same time, and he fell to the ground yelling, “Oh Lawdy help me, the bellboys done got me!” But no sooner had he hit the ground than the sting ceased, and as both men regained their composure somewhat, it suddenly dawned on them what had happened. They had strayed into the field of a neighbor who had put up, unbeknownst to them, an electric fence. Eventually, after disentangling themselves from the electrical monster, they made it to the road and a farmhouse and around midnight were able to call my anxious mother who had no clue where they were, but who was not unaccustomed to such events.

The whole episode made for a great story, which was often repeated around the big table at the camp house during hunting season, the chief venue for such stories. My father, who was always sat at the head of the table that accommodated about ten men—the acknowledged head and the chief storyteller–would hold forth. No one could match his knack for spinning a good yarn, shaping and rounding it in a way that always left you with a good laugh and an appreciation for the absurd. Cholly and snakes provided endless fodder for his stories.

A Snake in his Boot

And there were plenty of snake stories, with or without Cholly in them! I experienced a few of these myself. I do believe we lived in one of the snakiest places on earth. They were a part of our lives from early on and we became quite snake savvy about their ways at an early age. Still, there was always the unexpected. Once when I was riding horseback with my father through the same Skull Creek bottom we had to make our way through some Yaupon bushes, which we did by putting our heads down on the horses’ necks and letting our horses pick their way through the brush and vines. Our bodies would then act as a wedge passing the limbs and vines over us without unseating us from the saddles. We usually wore brush jackets and leggings for this purpose and we always had toe fenders (tapadores) on our stirrups so if we did get unseated our boots would not wedge in the stirrups, a very dangerous situation.

On this particular occasion, it had been very wet of late. The snakes in the bottom will often take to the brush and trees when this is the case. As Papa passed under a low-lying bush and put up his arm to brush aside the branches, a copper head, which was up in the branch, was dislodged and fell through the collar of his jacket. The jacket was open in the front, allowing the snake to pass easily through the jacket along the inside, but when he emerged a most improbable thing happened. He escaped the jacket but dropped into his right boot, his pants being tucked into the same in the fashion of all the old cattlemen. At this, papa, hollering in disbelief, jerked his horse so violently by the reins that he fell over to the side, allowing him to roll off in a flash. He quickly jerked off his boot and shook the snake out which slithered away as fast as he could, apparently as unnerved by the event as my father. Neither was any worse for the episode and miraculously the snake never bit. A student once asked me why cowboys wear chaps and I told him to keep snakes from falling in your boots. He thought I was joking. But the moral of the story was why fear the great unknown when there was so much close at hand to deal with?

But back to Cholly. Cholly made up for his mechanical ineptitude and other shortcomings with compensatory talents. He had a rich and unique take on human nature; a keen observer of people and their interactions. Nothing interested him more. He gave everybody a whimsical nickname, which was often a perfect distillation of traits, both physical and mental. As an example of the first, he named one of my friends “Ol’ Folks,” because he acted unnaturally mature for his years; or again, another man “Twist” for the funny way he walked, and the moniker stuck, at least behind his back. He nicknamed me Wiliker and the name has endured in the family ever since.

Cholly had had a most unusual upbringing. He had been raised by his great uncle, a former slave, on a river bottom farm not far from our place, a farm that is still in his family. His great uncle had been a manservant to a Confederate officer in Terry’s Texas Rangers during the Civil War, or, as local die-hards termed it, the War of Northern Aggression. The officer had given the river bottom farm to his uncle in recognition of his service and also in gratitude for the rest of the family who continued in loyal service on the home front during the war. Over the years a kind of settlement had grown up with several dilapidated shotgun houses from various members of the extended family clustered around an assortment of sheds and run-down outbuildings. Several generations lived here communally and the women would prepare breakfast and supper in a kitchen shack that was separate from the other buildings.

Cholly used to tell how his old uncle had continued to wear his confederate jacket and kepi until the day he died, and every morning had required the large passel of children who inhabited the compound to line up out front in parade formation for inspection. He would then march them to the communal kitchen for their breakfast. If anyone got out of step, he would crack the ten-foot bullwhip he carried for that purpose. The whole image is so absurd and improbable that I sometimes I think I must have dreamed it, but no, that is just as Cholly told it. And how entertainingly he had mastered the art of storytelling! He had an extraordinarily rich voice that he could modulate with perfect control to emphasize the narrative at just the right points. The underlying rhythm of his presentation became part of the story, which sucked you in and carried you along, and it always culminated in some absurdity that left you chuckling in disbelief and wonder.

Ned Boy

Like the story of another uncle who cooked whiskey on the side during prohibition, not unlike a lot of people in the county at the time, black and white, who found creative ways to make ends meet during the depression era. It must have been on a pretty grand scale because Cholly related how milk trucks would come down from as far away as Chicago with false compartments to transport the white lightning. The local sheriff and law enforcement were on the take, of course, but that’s another story. The real story was about his brother, Ned Boy, who always endeavored to walk the straight and narrow and avoid those distractions that would divert one from the path of righteousness. Yes, he was deeply religious and had taken to heart the threat of eternal damnation. Alone among the men who would gather from time to time around the still to sample the fiery sap of their labors, he had foresworn all strong drink and refused to partake; choosing instead to concentrate dutifully on the many tasks of the farm. The river bottom offered an abundance of rich black dirt that was perfect for the cultivation of corn and cotton. Every year, sizeable fields of both were planted and, as luck would have it, one of the fields spread out directly below the hill where the still was located. One day Cholly had accompanied his uncle to the barrelhouse where the finished product was stored when the two noticed quite an astonishing sight unfolding below them. Ned Boy was attempting to break the field below with a team of mules hooked up to a turning plow. But instead of going about the business of laying out the furrows neat and regular, he was whipping the mules to a frenzy, plowing loops and curves to a steady stream of unholy expletives. The poor mules didn’t know whether to hee or haw. Yep, you guessed it. Ned Boy had succumbed to temptation and partaken of the forbidden juice. Cholly’s hilarious description of his brother’s antics and his reproduction of the calls of his inebriated brother as he tried in vain to get the mules to plow a straight furrow, resonate in my memory to this day.

We grew up hunting and fishing, and Cholly was often a part of that. My brother and I liked to go squirrel hunting in the cottonwood and pecan bottoms along the Colorado River on what we called the Grace Place, named after old Dr. Grace, who had had a plantation there before the Civil War, and was later killed in a shoot-out in Weimar by an irate husband whose wife he had seduced, but that is another story. Anyway, my brother and I would take the ranch jeep on a Sunday afternoon and go pick up Cholly in the dilapidated and unpainted shanty he lived in along with his wife and two sons across the tracks in the nearby railroad town of Glidden, and head for the bottom. My brother usually did the shooting with his trusty Winchester semi-automatic 22 which he had outfitted with a scope. Cholly was the spotter and nobody could pick out a squirrel better. It was uncanny. He would point one out way up in the fork of a pecan tree, just the bump of his head and two pointy ears showing. It often took us a while to hone in on what he had already spotted from a distance from the back of the jeep. We were conscious of his superior talents and secretly envious. The combination of his eyesight and my brother’s marksmanship was effective though and we usually ended up with a good mess of squirrels, which Cholly would take home to make squirrel stew. That was his pay-off for putting up with a group of teen-age White boys.

Picking Cotton and Playing Practical Jokes

Cholly also had a couple of mangy coon dogs that he kept chained to a large live oak tree in his back yard. Once deer season was over and there was a good moonlit night with frost on the ground we would do a coon hunt with Cholly along Skull Creek bottom, an incredibly diverse and rich natural habitat, rich with coons and other wildlife. Still, we rarely caught any, but that was beside the point. The usual method was to drive to a spot where a natural clearing edged the dense hardwood bottom not far from the creek bed itself. Here we would turn the dogs loose. In the meantime, waiting for the dogs to pick up a scent, we would gather up dead live oak limbs and build a big roaring bonfire. With the dogs baying in the distance, their rich tones filling the woods and echoing among the trees, we would sit at the edge of the crackling fire and Cholly would began to relate stories from his youth when he travelled the South following the cotton crop. It was a rough life in the heart of the Old South during the highpoint (or low point, as the case may be) of the Jim Crow era. Cholly would allude to the indignities and injustices of this, but in a guarded and circumspect way. The first cracks in the edifice were beginning to appear, but it was still segregation, after all, and even among ourselves there were certain lines you didn’t cross and certain taboos you didn’t breach. It was really only much later that I realized how deeply Cholly had chafed and burned under the indignities and injustices that the Jim Crow South had forced upon him, but that is another story. Anyway, sitting next to the fire, Cholly would tell stories from his youth and the cotton circuit, and one had to read between the lines. Most of the stories revolved around sexual adventures of one kind or another, and this is where the real contrast came into play. Remember, I used the big word contrapuntal. Cholly offered a different take about the birds and bees from the standard party line that we were getting in the classroom and from the pulpit; and for a group of high school boys trying to come to terms with the testosterone flowing in their veins, this was very interesting and informative. I can remember several of his stories.

[Warning: for younger and more sensitive readers, parental discretion is advised.]

They had been picking cotton somewhere in Georgia. They had taken their noon meal in an abandoned and dilapidated two-story barn. After eating lunch, one of the boys had gone upstairs, laid down in a bed of old hay, and quickly fallen asleep. He was a deep sleeper. When they went to get him, they noticed by a certain unmistakable protuberance through his overalls signifying that he was enjoying a very pleasurable dream. They decided to play a practical joke. They gently unbuttoned his fly, liberating his excited member. They then made a loop in a rice string and gently attached it. They then fed the string down the stairwell and began mildly and rhythmically tugging it, soon achieving the desired effect of which I will leave to the reader’s imagination. They exploded in laughter, but the poor victim of this practical joke was less than happy. As Cholly put it, “that Nigga’ wanted to fight!”

There were many stories along these lines but Cholly’s sexuality also led him to offer encouragement to my brother and I. Living out in the country, we only had a few neighbors, one of which was a German sharecropper by the name of R____—one of the last of the sharecroppers in the Colorado River bottom. They lived in a very modest, unpainted clapboard house about a mile from our house as the crow flies and set back from the public road a good mile on a crest overlooking the river bottom where the father still planted cotton and corn on shares. They still lived as if in the 19th century: their house an unpainted, clapboard structure; no electricity and no phone. Still, the family seemed content: they ate well, were always well-groomed and neatly dressed, simply and modestly to be sure, often in home sewn clothes, but always tidy and clean. Despite their poverty, the family held its head high and was respected in the community. Albert, the old man, was quite a character, but that is another story. For the moment two things need to be mentioned that caught our attention as young adolescents. First, they had a pet deer (as we did) but they had managed to train their pet to do a most extraordinary thing: it would go down every day to the mailbox on the public road (a mile’s trip, you will remember) with a leather pouch around it’s neck and wait for the mailman. The mailman would give the deer a sweet and deposit the mail in the pouch around the deer’s neck, which the deer would then dutifully return to its human family. How they got the deer to do this is beyond me.

But this story, as interesting as it was, wasn’t what interested Cholly. The family had three daughters who were more or less the same age as my brother and I. They presented quite a sight when all three lined up to wait for the school bus that carried us all to the school in Columbus. The oldest, L___, was tall and skinny as a bean pole, while the youngest, S__, was short, round and fat, but V___, the middle one, was a picture of perfection, with reddish blond hair, striking blue eyes, and a Hollywood figure.

For the life of him, Cholly could not understand why my brother and I did not take full advantage of this situation, and he was constantly egging us on. For Cholly life was reduced to fundamentals. He believed that there were only a few basic experiences and everything else was a variation thereupon. Cholly wanted us to realize that sexual attraction was basic and it was high time we started showing interest in the subject and taking advantage of what was at hand.

To be continued….

[1] There was a five acre enclosure next to our house that included the large hay barn/saddle house, several other sheds, and the pens for working cattle that we called the ‘runaround.’