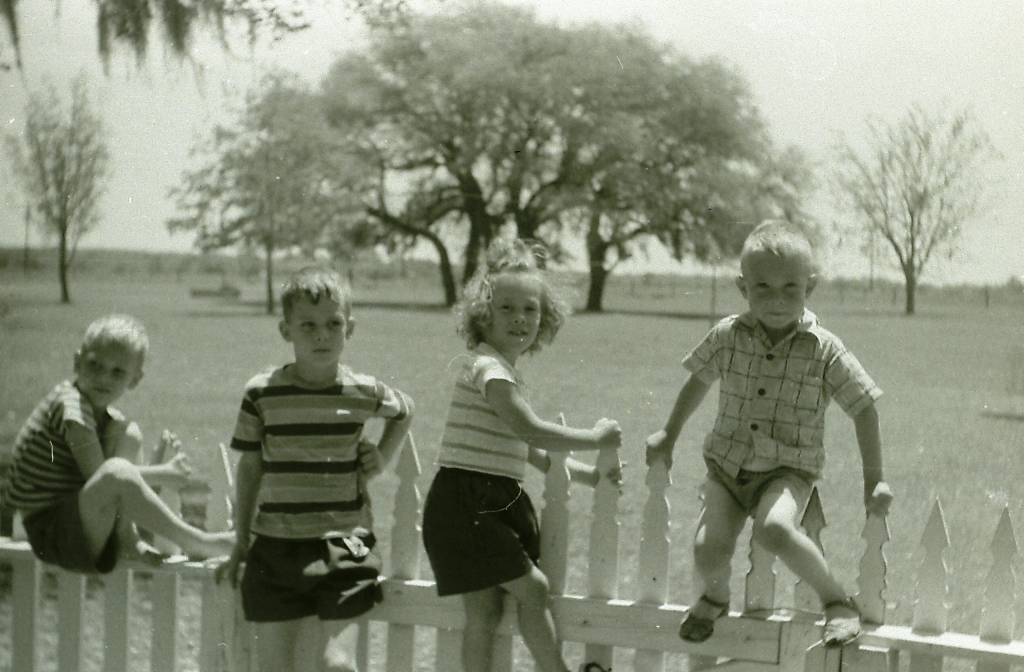

Me, my brother John, my cousin Paulette and our neighbor Gordon (G-Boy) Richter

Me, Butterball, my brother John, and neighbor Peggy Lampkin

I am an old man now with a sensibility that certainly frets about my grandchildren’s future but one that can still take delight in my own youth, even though, admittedly, I still cringe at the thought of the many shenanigans I was involved in. But through both the good and the bad my childhood was full and rich, no question about that, and the more I think on it, the more I realize it was pure Texan, but from an era that has now vanished irretrievably in the rear view mirror, although this fact did not really sink in until many years later. At the time I thought it was normal to grow up semi-wild, like a Comanche Indian, with thousands of acres to roam at will on; to spend most of my youth in the river bottoms and post-oak savannah of south-central Texas, to develop an easy familiarity with the critters and varmints, the horses and cows, the insect and plant life, and to come to adulthood in a human-scape as rich and varied as the landscape.

It was all captivating, but the human-scape was perhaps the most intriguing of all for me. It included a fascinating array of characters of all classes and colors; men who fit no mold and were often wonderfully eccentric and sometimes impishly irreverent. Citizens of German, Czech, and Anglo descent filled out the white population in roughly equal numbers, which created a unique dynamic within itself, but added to this was a substantial black population, which provided the most trenchant interaction.

Our little rural community of Smith Point replicated on a small scale the aforementioned demographic make-up of the county and this part of the state: Anglo, German, Czech and African American. At the time, it should be noted, there were very few Hispanic families in the county. Our own family counted as the Anglo component mainly because our immigrant antecedents were much older than the other groups and, in fact, were pre-Revolutionary War on both sides.

Our closest neighbors, the Richters, were of German ancestry. The grandparents, the grown son and wife, and their two sons shared the modest but neat farmstead across a country gravel road from our house. Emil, the old patriarch, still preferred German to English. His son Gordon and his wife Hildegard had two sons and the oldest of them, whom we called G-Boy, was my age, a constant playmate, and almost like a brother. This relationship was strengthened by the fact that we shared cousins, since my uncle had married into the family, and his children were first cousins to us both.

Further down the gravel road that ran between us, was a Bohemian family by the name of Kneblik, a wife and husband, who were childless, and who had set up a small farm, although both worked day jobs in the nearby town of Columbus. Although both native born, they preferred to speak Czech at home and the husband Nick only spoke broken English with a heavy Czech accent. Margie liked to bake Kolaches on the weekend. My brother and I and G-boy often ran down the road to sample these wonderful Czech pastries. We had to tell her, “Děkuji!” which means “thank you” in Czech. We also learned many German phrases since so many people knew the language and regularly sprinkled their conversations with words and phrases.

Even further down the gravel road was a freedmen’s colony, and the black people who lived there still spoke with a heavy accent called Gullah, which was hard for many white people to understand who had not grown up with it. There were several of these colonies sprinkled about in the county and usually not far from the Colorado River bottom where their slave ancestors had toiled on the large cotton plantations that spread up and down the river in the antebellum period. They had withdrawn to these enclaves after emancipation. This particular “colony,” which we called Frogtown, was dominated by the Scott and Field families and included five or six shotgun shanties clustered on a ten or fifteen acre tract. The families had a somewhat communal organization. I can remember a large cast iron pot in the center where the families would do their Saturday washing or render hogs for soap. The slave plantations, which had spread up and down the river in the antebellum period, accounted for the substantial black component, which had reached a high point of 45 % of the total population by the 1860 census. By the mid twentieth century this percentage had shrunk considerably as many blacks chose to “get out of Dodge,” so to speak, and seek better opportunities in the big cities or in the US military. Those who remained eked out an existence for the most part as domestics (women) or as farm and ranch laborers (men).

Ironically, this led to a surprising degree of interaction on a daily basis between the races despite the rigid system of segregation that prevailed and that was designed to separate the races. It was still very much the Old South in rural Texas when I was coming up. Jim Crow reigned, and the old plantation mentality still prevailed among the white populations, but within this context meaningful and enduring relationships often developed that in some cases went back generations.

Our own family illustrates this perfectly. We had a relationship with the freedmen’s colony down the road from our home. Claude Fields had worked for my father before I was born, but first Lizzie Scott, the matriarch of the clan, and subsequently her daughters and granddaughters worked for my mother as domestic help. It went beyond that. My mother was the principal at the nearby Glidden rural school so when my brother and I were yet babies, Lizzie was our wet nurse and baby sitter while mother was at work, a kind of second mother. It was a patron system. Black people had no chance for equal justice back then, so families developed strong relations with important white families as a means of shielding themselves. “You mess with me and you be messing with Mistah Kearney,” that sort of thing.

The black component added another dimension and through the rich interplay of all these groups and characters who inhabited my youth, I developed an unusual facility, namely the habit of seeing and understanding the world through completely different eyes at the same time, and to accept the varied views as equally valid though they often seemed incompatible on the surface. This habit of mind reinforced my skeptical nature and has since crystallized into a philosophy for understanding the world and interpreting history. I call it the complementary view of life. I think it is a worthwhile habit of mind to cultivate because even as it broadens one’s own perspective, it encourages tolerance and discourages the narrow tribalism that is a source of so much evil in the world. In my own case it helped me in time to shed the ethnic and religious prejudices that had been inculcated in me from an early age. The ‘complementary view of life’ is the common denominator to all the stories included below.